Hello again, friends and readers. I know it’s been a minute since I put up new post, but as anyone who’s been paying any attention to the news can attest, it’s been a hell of a year.

For my final blog post of this crazy year, I’d like to revisit a topic I spent hours discussing with friends and fellow fans some (yeesh) dozen years ago, now: The fan response to Christopher Nolan and Zack Snyder’s (and to a lesser extent, David Goyer’s) Superman film, Man of Steel.

The reason this topic has reared its head is because there’s a new Superman take coming out next year courtesy of James Gunn, the director responsible for the wildly popular and unserious Guardians of the Galaxy films for Marvel. It’ll be called just Superman, and once the first trailers started appearing online, fans did what fans do, and the argument about what some folks have taken to referring as “Snyder’s Superman” reignited itself all over the internet again.

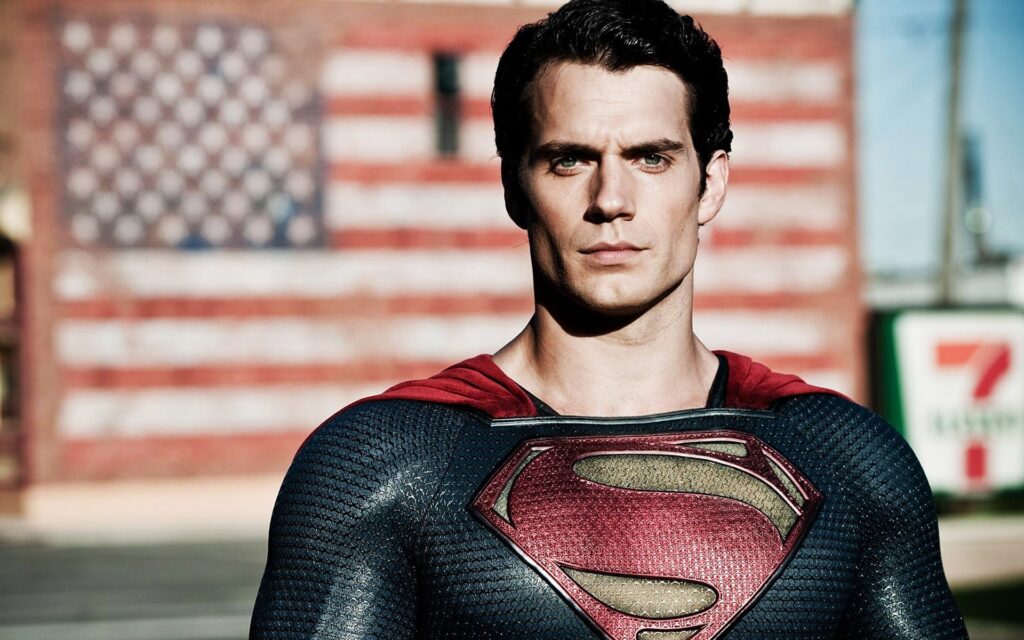

While individual fans have individual criticisms of the Snyder-helmed 2013 effort, the end result is that the film is regarded widely as “divisive”; specifically. ‘Divisive’ is the term you see most often ascribed to the film and its impact on audiences in the years since its release, and not merely because it gave rise to a whole series of Snyder-involved DC films that likewise featured what was ostensibly the same character, played by the same actor (in this case, Henry Cavill).

First, let’s take a look at the choices and story elements that led to that reputation.

The Divide

The source of the lion’s share of this “divisiveness” you hear fans talk about stems from the following choices the filmmakers and producers made. (After 12 years, I think it’s safe to assume no one’s being spoiled here, by me, for the first time, but just in case… spoilers ahead.)

- Superman Kills: At the end of Man of Steel, Superman is essentially forced into killing General Zod, the fellow Kryptonian genetically engineered to see any act of violence or destruction as justifiable when done in the pursuit of securing the future of his people.

- Collateral Damage: During the climactic fight sequence, two Kryptonians duking it out over Metropolis causes destruction that presumably leads to more than a few fatalities and plenty of injured humans (not shown on screen), when the traditional view of the character would have seen Superman trying to lead Zod away from populated areas.

- Serious Tone: As a follow-up to Nolan’s Batman trilogy, Man of Steel has a tone that’s grittier and more grounded than the lighter tone of previous adaptations and that of the Marvel cinematic universe. This tone was (and still is) referred to as “Grimdark”, a term used pejoratively by those who wanted and were expecting to receive that lighter tone.

- The Death of Pa Kent: During a flashback, we see Superman’s adoptive father choose to allow himself to be blown away by a sudden tornado rather than see a teenaged Clark out himself as an alien to the entire world, under the auspices of the idea that neither Clark nor the world is ready for the revelation and the consequences that would ensue.

The Rebuttal

I and others litigated these points of divisive concern back in 2013 (and successfully overall, I think), but as a quick reminder, let us look at the relative merits of these points in turn:

Superman Kills: The death of Zod in Man of Steel is not remotely the first time Superman has killed someone in a Superman story. Yes, it is very much the character’s overarching principle not to take life if he can avoid it, but it’s hardly something that originated with these filmmakers. Superman kills, but only when left with absolutely no other viable alternative. That is canon.

More to the point, it’s exactly what DC Comics (and its parent company, Warner Brothers) wanted from the story. Knowing full well that a segment of the fanbase carried an idealized view of the character, Nolan had reservations about the choice and he raised those concerns with those who owned the character and commissioned the film. Those people are the ones who said the call was both thematically coherent and in keeping with their view of the developing DC cinematic universe, especially as would-be counterpart to what Marvel was doing with theirs. Those folks overruled Nolan and requested the killing of Zod not be excised from the script.

People can dislike the choice all they want, but any allegation that it was a function of Zack Snyder being a dudebro, or obsessed with his own Grimdark, or anything of that nature, is false, as is any contention that Superman would absolutely never, ever, ever kill anyone.

Collateral Damage: If you go back and actually watch that fight sequence with a critical eye, you’ll see what other critics and I saw, which is that Superman does try to lead Zod away from congested areas — at one point, taking the fight to the top of an abandoned construction site, and thereafter, taking the fight into the air high above the streets in his attempt to avoid human bystanders — but soon discovers that the fight venue isn’t really up to him. It’s up to Zod. And as established repeatedly throughout the film, Zod’s intent is to literally wipe out humanity so that Krypton can be reborn on Earth. At one point, just to really drive the point home to the audience, Zod’s lieutentant says to Superman, “For every human you save, we will kill a million.”

And to those who think Superman should/would have found a way to lead Zod fully away from anyone who could possibly be caught up in such a clash of titans, I would simply ask this:

How?

What would these folks suggest Superman do? Use harsh language? “Yo’ momma” jokes? How, pray tell, does Superman successfully lead or lure Zod away from the very objective he’s there to fulfill? The answer is, he can’t. He can only fight Zod where Zod exists to be fought. And as Zod tells him multiple times, the only way to get Zod to leave Earth alone is to kill him.

The Serious Tone: First and foremost, the character depicted in Man of Steel is absolutely the Superman we know and love. In his first 15 minutes on screen, the character saves all the workers on an oil rig from certain death, an entire busload of children from drowning, and a waitress from being harassed and demeaned on the job. The guy is every bit our Superman.

Not only did the owners of the character and property decide that they wanted to distinguish their cinematic universe from their primary competitor’s cinematic universe by continuing on in the vein of the recently completed and explosively successful film trilogy featuring a character from the same universe — which means that audiences were never going to get anything but a grittier take on the character during that era, regardless of who ended up writing or directing the specific script — but furthermore, this idea that there was never a Superman tale prior to the film that went a similar direction is belied by a simple review of the comic’s history.

Again, nothing DC and the filmmakers did with Man of Steel is anything that DC hadn’t already paved the way for in prior canon. And more broadly, it’s always been a feature of comics and comic-universe characters that the material can be altered to suit new takes, new writers, and new eras of cultural advancement. Such pliability is a core feature of the form, even moreso than in other arenas of conceptual narrative, where it’s often given more leeway by audiences than what they’ll grant to this particular character, despite the prevalence of adaptive variation.

There’s another, even bigger problem with this complaint, but I’ll get to that in a second.

The Death of Pa Kent: Leaving aside the fact that Pa Kent choosing to be carried away by a tornado rather than risk his son’s life and happiness was thematically perfect for this particular piece of art, there’s another thing critics of the scene/choice never seem to take into account:

While the traditional Superman might, indeed, have ignored his father’s wishes in that moment and swooped in to save him, anyway, the character in that sequence was not Superman, yet. He was a teenaged kid, not a superhero. That’s partly why Pa Kent made the choice he did, you know? And the idea that that teenaged kid was momentarily paralyzed by confusion and the fear of defying his father’s express wishes is more than sufficient grounds to render the sequence acceptable, especially inside the context of the story they were actually telling.

On Divisiveness

As works of fiction, individual audience members can get whatever they want out of pieces of Superman media, be they comic books or live-action films. As art, though, what Superman is, fundamentally, is the world’s most popular and commercially successful metaphor for Jesus. That is both the source of the idea and, thanks to the Christian-dominated culture for which it was created, the source of its immense and enduring success. That is what Superman is.

I’ve given this subject a great deal of thought and, well, I can’t imagine anything more divisive than the matter of whether or not a child born to a mortal woman was actually and in fact, God. And the fact that billions of people are either fully convinced of the idea or very open to the idea, while billions of other people are either firmly unconvinced of the idea or else strongly skeptical of it, would seem to definitively illustrate the essential divisiveness of the core idea.

For all of what people seem to want him to be, Jesus remains an intensely divisive figure.

When you look at the complaints people have about the Christ analog in Man of Steel, what you see at the heart of all those complaints is disappointment. In some cases, these people know all the facts in the rebuttals I mention above; they know Superman killed canonically, and they know the film’s choices are artistically coherent. What they are truly bemoaning is the fact that, in this particular Superman tale, the reality failed to live up to the ideal for them. Now, there’s a lot that can be said on that particular matter, but for my part, I think I would start with this:

If you think you’re disappointed in how the reality of Christ and his legacy have failed to live up to the ideal, try to imagine how the people of the Middle East must feel.

The biggest irony of this disappointment is that Jesus, himself, failed to live up to the ideal that this particular segment of fans would like to think he embodies at all times through his fictional analog. If you believe the gospels, it was Jesus who said:

“Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother.” (Matthew, 10:34)

Don’t look now, but some would go so far as to call that attitude “divisive”.

I must also make mention of the fact that this very same cinematic universe (though admittedly not Man of Steel, itself) contains what is probably the most divisive casting decision in the history of American cinema: Warner gave the role of Wonder Woman, a worldwide role-model to kids, to someone who served as a soldier in an illegal occupation army and once threatened to destroy the career of someone who sought to expose her male friend for raping her one night.

Let me be crystal clear on this score: Anyone who complains about Man of Steel while remaining silent about the casting of Wonder Woman in the same cinematic universe, is a person whose opinion on these things means absolutely nothing. (And from what I’ve seen, the overlap on that Venn diagram is substantial, for whatever that fact may indicate or reveal.)

Gal Gadot does not deserve to come anywhere near the role of Wonder Woman, full stop. For those intent on talking divisiveness, I might suggest they start there.

As an aside, I don’t find “divisive” to be an especially damning criticism of art. When Stanley Kubrick made a film out of Lolita, some people went so far as to call for his arrest, accusing him of being as bad as the thing his art was critiquing. When he made a film out of A Clockwork Orange, that film was outright banned in a few countries; once again, because people confused artistic critique of a subject with the artist’s personal embrace thereof.

And that guy was the best to ever do it in his medium.

On the Value of Quality

In the interests of disclosure, my critical opinion of Man of Steel falls in line with that of many other film critics and buffs, which is that it’s the best actual film of all the cinematic adaptations of the character we’ve gotten to date, and easily Snyder’s best film, as director. It also happens to be my favorite film of the DCU so far, beyond even the Nolan Batman films, which I like a lot.

As such, let’s conclude by comparing the responses to Man of Steel to how people respond to Superman films that don’t trigger these same complaints about the film’s tone and choices.

If it were purely a matter of filmmakers properly adhering to the perceived ideal of the figure — to the traditional, would-be uplifting view of Superman — then surely Bryan Singer’s 2006 take, Superman Returns, would rate far higher in its reception among fans and critics than does Man of Steel. Yet, according to IMDb (the most popular movie database online), as well as on other review sites and critical aggregators online, it rates significantly lower than Man of Steel does, even though that one was made expressly as a love letter to the beloved 1978 adaptation and even though it carries none of the perceived fan baggage of the Nolan-and-Snyder take. Indeed, Man of Steel doesn’t even rate lower than that same beloved 1978 version, which is regarded widely as the crystalline ideal for the character, but which, as a film, doesn’t actually age so well.

At the end of the day, the so-called divisiveness over Man of Steel wouldn’t even be an issue if it was a bad film, artistically and technically. People would simply chuckle and relegate the film and all discussion of it to the dustbin of comic adaptation history — a receptacle that is by this point near to overflowing with various lackluster and otherwise underwhelming efforts.

The fact that it’s as good as it is is the very reason we’re even having this debate, 12 years on.

I am painfully aware that critical quality is not everyone’s jam like it is mine, but the problem with failing to appreciate if not prioritize quality is that it leads to a Pandora’s box of derived issues, all of which are rendered defensible only via the sadly anemic stand of “It’s not what I wanted”.

Should the film’s high quality as a film fail to overcome your disappointment at the reality failing to live up to the ideal, then I would ask you to hold the source material equally responsible for that, and not focus so much on a fictionalized version not giving you exactly what you wanted.

As a story featuring the world’s most popular and commercially successful metaphor for Jesus, Man of Steel is unequivocally the fairest fictional representation of its source material ever put to film. Its depiction of the character’s hopes, beliefs, and flaws offers a view that falls squarely in line with what we know of the real-life figure, from his highest ideals to his views on doing harm.

And if that’s not what people wanted from their tale of a Christ, maybe those people should think about altering the reality of the thing being discussed instead of attacking the art expressing it.